Declaring C and N Fields

This article will discuss character strings. When creating programs, fields defined as character strings are almost always used. In SAP, there are two elementary data types used for character strings. These are data type C, and data type N.

Data type C.

Data type C variables are used for holding alphanumeric characters, with a minimum of 1 character and a maximum of 65,535 characters. By default, these are aligned to the left.

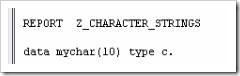

Follow along and create a new program. From the ABAP Editor’s initial screen, create a new program, named “Z_Character_Strings”. Title this “Character Strings Examples”, set the Type to ‘Executable program’, the Status to ‘Test program’, the Application to ‘Basis’, and Save.

Create a new DATA field, name this “mychar” and, without any spaces following this, give a number for the length of the field in parentheses. Then, include a space and define the TYPE as c

This is the long form of declaring a type c field. Because this field is a generic data type, the system has default values which can be used so as to avoid typing out the full length of the declaration. If you create a new field, named “mychar2” and wish the field to be 1 character in size, the default field size is set to 1 character by default, so the size in brackets following the name is unnecessary. Also, because this character field is the default type used by the system, one can even avoid defining this. In the case of mychar2, the variable can be defined with only the field name. The code in the image below performs exactly the same as if it was typed “data mychar2(1) type c”:

In the previous article on calculations, the table “zemployees” included various fields of type c, such as “zsurname”. If one uses the TABLES statement followed by zemployees, then by double-clicking the table name to use forward navigation and view the table, one can see that the “surname” field is of data type CHAR, with length 40. This declaration can be replicated within the ABAP program:

Return to the program, and in place of mychar2, create a new field named “zemployees1”, with a length of 40 and type c. This will have exactly the same effect as the previous declaration. Referring back to previous article, another way of doing this would be to use the LIKE statement to declare zemployees (or this time zemployees2) as having the same properties as the “surname” field in the table:

Data type N.

The other common generic character string data type is N. These are by default right-aligned. If one looks at the initial table again, using forward navigation, the field named “employee”, which refers to employee numbers, is of the data type NUMC, with a length of 8. NUMC, or the number data type, works similarly to the character data type, except with the inbuilt rule to only allow the inclusion of numeric characters. This data type, then, is ideal when the field is only to be used for numbers with no intention of carrying out calculations.

To declare this field in ABAP, create a new DATA field named “znumber1”, TYPE n. Again, alternatively this can be done by using the LIKE statement to refer back to the original field in the table.

String Manipulation

Like many other programming languages, ABAP provides the functionality to interrogate and manipulate the data held in character strings. This section will look at some of the popular statements which ABAP provides for carrying out these functions:

- Concatenating String Fields

- Condensing Character Strings

- Finding the Length of a String

- Searching for Specific Characters

- The SHIFT statement

- Splitting Character Strings

- SubFields

Concatenate

The concatenate statement allows two character strings to be joined so as to form a third string. First, type the statement CONCATENATE into the program, and follow this by specifying the fields, here “f1”, “f2” and so on. Then select the destination which the output string should go to, here “d1”. If one adds a subsequent term, [separated by sep] (“sep” here is an example name for the separator field), this will allow a specified value to be inserted between each field in the destination field:

Note: If the destination field is shorter than the overall length of the input fields, the character string will be truncated to the length of the destination field, so ensure when using the CONCATENATE statement, the string data type is being used, as these can hold over 65,000 characters.

As an example, observe the code in the image below.

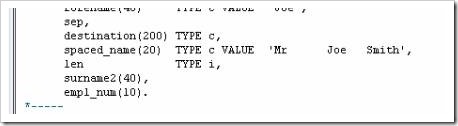

The first 3 fields should be familiar by now. The fourth is the separator field, here again called “sep” (the size of sep has not been defined here, and so it will take on the default which the system uses – 1 character). The last field is titled “destination”, 200 characters long and of data type c.

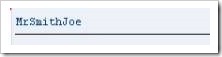

Below this section is the CONCATENATE statement, followed by the fields to combine together into the destination field. The WRITE statement is then used to display the result. Executing this code will output the following:

Note that the text has been aligned to the left, as it is using data type c. Also, the code did not include the SEPARATED BY addition, and so the words have been concatenated without spaces. This can be added, and spaces will appear in the output:

Condense

Next, the CONDENSE statement. Often an ABAP program will have to deal with large text fields, with unwanted spaces. The CONDENSE statement is used to remove these blank characters.

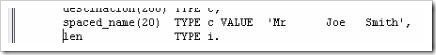

Now, observe the code below:

This should, of course, be mostly familiar from the last section, with the addition of the new, 20-character “spaced_name” field, with large spaces between the individual words. Below we have an example of using the CONDENSE statement using our new variable:

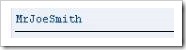

The CONDENSE statement will remove the blank spaces between words in the variable, leaving only 1 character’s space:

NO-GAPS

An optional addition to the CONDENSE statement is NO-GAPS, which as you may guess, removes all spaces from our variable.

Find the Length of a String

To find the length of a string, a function rather than a statement is used. Added beneath the previous data fields here, is a new one titled “len”, with a TYPE i, so as to just hold the integer value of the string length.

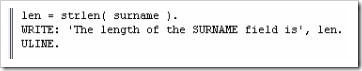

The code to find the length of the ‘surname’ field and display it in the ‘len’ field appears like this, with “strlen” defining the function:

The output, then, will appear like this:

Replace

Below I have created the “surname2” field and is 40 characters in length. Note that no TYPE has been defined, so the system will use the default type, c:

Some text is then moved into the field after which the REPLACE statement is used to replace the comma with a period:

One thing to note here is that the REPLACE statement will only replace the first occurrence in the string. So if, for example, the surname2 field read “Mr, Joe, Smith”, only the first comma would be changed. All occurrences of comma’s could be replaced by making use of a while loop, which will be discussed later on.

Search

Next, a look will be taken at searching for specific character strings within fields. Unsurprisingly, the statement SEARCH is used for this.

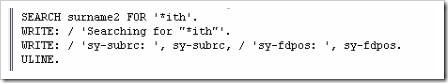

All that is needed is to enter SEARCH followed by the field which is to be searched, in this instance the surname2 field. Then the string which is to be searched for, for example, ‘Joe’:

Note that here no variable has been declared to hold the result. In the case of the SEARCH statement, two system variables are used. The first is “sy-subrc”, which identifies whether the search was successful or not, and the second is “sy-fdpos”, which, if the search is successful, is set to the position of the character string searched for in surname2. Below, a small report is created to show the values of the system variables.

SEARCH Example 1

The first SEARCH statement, below, indicates that the surname2 field is being searched, for the character string ‘Joe ‘. The Search statement will ignore the blank spaces. The output will show the string being searched for, followed by the system variables and the value results. In this case, the search should be successful.

SEARCH Example 2

The next example is very similar, but the full stops either side of ‘.Joe .’ mean that the blank spaces this time will not be ignored and the system will search for the full string, including the blanks. Here, the search will be unsuccessful, as the word ‘Joe’ in the Surname2 field is not followed by four blank spaces.

SEARCH Example 3

This third search uses a wild card character ‘*’ and will search for any words ending in ‘ith’. This, again, should be successful.

SEARCH Example 4

The last example also uses the wild card facility, this time to search for words beginning with ‘Smi’, which again should be successful. Compare the places in the code where the * appears in this and the previous example.

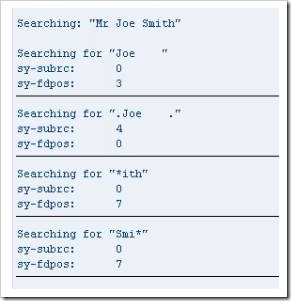

Run a test on these searches, and output returns as follows:

When the sy-subrc = 0 this refers to a successful search. When sy-subrc = 4 in the second example this indicates that the search was unsuccessful.

In the first search, the sy-fdpos value of 3 refers to the third character in the surname2 field, the offset, and the search term appears one character after this. The failure of the second search means that a 0 is displayed in the sy-fdpos field. The value of 7 in the sy-fdpos fields for the final two searches both mean that the word ‘Smith’ was found, corresponding to the search terms, and that the searched word appears 1 character after the offset value.

Shift

The SHIFT statement is a simple statement that allows one to move the contents of a character string left or right, character by character. In this example, a field’s contents will be moved to the left, deleting leading zeros. Declare a new DATA variable as follows: “empl_num”, 10 characters long, and set the content of the field to ‘0000654321’, filling all 10 characters of the field:

Using the SHIFT statement, then, the 4 zeros which begin this character string will be removed, and the rest moved across to the left. Type the statement SHIFT, followed by the field name. Define that it is to be shifted to the left, deleting leading zeros (don’t forget the help screen can be used to view similar additions which can be added to this statement). Then include a WRITE statement so that the result of the SHIFT statement can be output. To the right of the number here, there will be four spaces, which have replaced the leading zeros:

If no addition to the SHIFT statement is specified, the system will by default move everything just one character to the left, leaving one space to the right:

The CIRCULAR addition to the SHIFT statement will cause, by default, everything to move one space to the left again, but this time the character which is displaced at the beginning of the statement will reappear at the end, rather than leaving a blank space:

Split

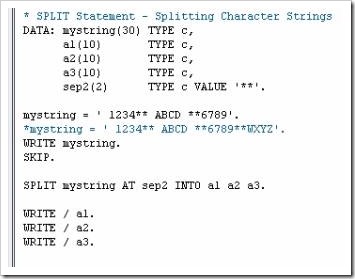

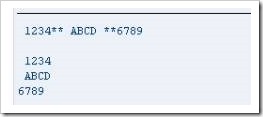

The SPLIT statement is used to separate the contents of a field into two or more fields. Observe the code below:

The first section contains several DATA statements, “mystring”, “a1”, “a2”, “a3” and “sep2”, along with their lengths and types. “Sep2” here is a separator field, with a value of ‘**’.

“mystring” is then given a value of ‘ 1234** ABCD **6789’, followed by a comment line (which the program will ignore), then a WRITE statement, so that this initial value appears in the output followed by a blank line, using the SKIP statement.

The SPLIT statement appears, followed by the name of the string which is to be split. The AT addition appears next, telling the program that, where “sep2” appears (remember the value of this is ‘**’), the field is to be split. Following this, the INTO then specifies the fields which the split field is to be written to. The slightly odd positioning of the spaces in the value of “mystring” will, when the statement is output, make clear the way that the SPLIT statement populates the fields which the data is put into. Execute the code, and this is the result:

You can see that the initial field has been split into a1, a2 and a3 exactly where the ** appeared, leaving a leading space in the first two fields, but not in the third. Additionally, on closer inspection there are blank spaces following the numbers in each field up to its defined length, which is 10.

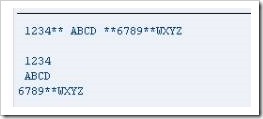

This next example shows the initial value of “mystring” now is made into a comment line, and the comment line becomes part of the code:

‘mystring’ now contains the original contents plus a further set of characters. While the contents are still to be split into 3 fields, the data suggests it should be split into 4. In this case, with less fields than those defined, the system will include the remainder of the string in the final field. Note that if this field is not long enough for the remainder, the result would be truncated.

SubFields

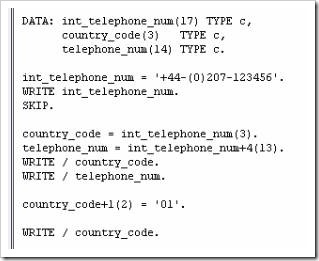

Within ABAP, you have the option of referring to specific characters within a field. This is referred to as processing subfields, whereby a specific character’s position within its field is referenced. Again, observe the code below:

To start with, new DATA variables are declared, “int_telephone_num”, “country_code” and “telephone_num”, along with lengths and types. Following this, a character string is assigned to int_telephone_num, a WRITE statement for this string and a blank line.

Next, the subfield processing appears. The first line states the country_code field is to be filled with the first 3 characters of the int_telephone_num field, indicated by the number in brackets.

Then, the field telephone_num is to be filled with 13 characters of the int_telephone_num field, starting after the 4th character. The +4 part of the code here refers to where the field is to begin. Then we have WRITE statements for both of the fields.

This last example indicates that the specific characters of int_telephone_num moved to the country_code field will be replaced, after the first character, by the literal, 2-character value ‘01’, showing that a subfield can itself be edited and updated without changing the initial field. The results should look like this:

Subfields are regularly used in SAP to save time on creating unnecessary variables in memory. It is just as easy to use the subfield syntax.